- First analysis, published or private, that questioned the financial viability of the Texas Air Corporation.

- Published when the consensus of the business media and industry analysts was a strong buy for Texas Air’s key subsidiary, Continental Airlines.

- Within two years of this article, Continental Airlines was in bankruptcy and Texas Air dismantled.

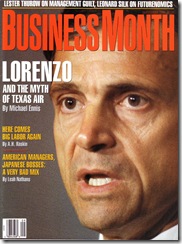

Frank Lorenzo built the world’s biggest airline company on reckless price cutting, government aid and lots of debt. He will need a miracle to keep it flying.

by Michael Ennis

When Frank Lorenzo, the wiry, reserved chairman of Texas Air Corporation, confronted a Washington news conference in June, he was smiling at circumstances that would have wiped the grin off most CEOs’ faces. True, Texas Air’s two key subsidiaries, Eastern and Continental airlines, which together comprise the free world’s largest commercial airline fleet (650 aircraft), had just passed an unprecedented investigation by the Department of Transportation into its safety compliance and fiscal fitness. But that was the only bright spot in a gathering storm. The department had added an important caveat to its report, warning that Eastern’s troubled labor-management relations could cause serious safety problems in the future; the U.S. House of Representatives had a resolution in the works that would continue scrutiny of Texas Air; and House Aviation Subcommittee members hinted they might disagree publicly with some of the DOT’s conclusions. Eastern’s unions already had, calling the report a “whitewash,” and financial analysts pointed out that the DOT, which described the figures it used as “optimistic,” had glossed over the liquidity crunch. Finally, beyond the purview of the investigation was the long-term outlook: Lorenzo’s $8.4 billion air empire was so deeply in hock it would need at least a billion dollars this year just to service its debts.

It is easy to assume that Lorenzo, long the recognized standard-bearer for the free-market conquest of the aviation industry, wouldn’t have it any other way. He has been credited—not always accurately—as the first airline chief to offer discount fares, the first to attempt a hostile takeover of another airline and the first to take a solvent airline into bankruptcy to abrogate onerous labor agreements. An undisputed wizard of leverage and a relentless proselytizer for unfettered commerce, Lorenzo has become not only the personification of airline deregulation but also a bankable superstar among ‘80s business celebrities.

Unlike many of his fellow corporate luminaries, Lorenzo, the man, has remained a mystery; he rarely grants interviews and has steadfastly refused to answer personal questions. When he does reveal himself, it is in a curiously utilitarian fashion: He wants to be seen as a lean and hungry cost cutter, for example, so we learn that he competes in marathons; he protests that he isn’t a union buster, so we hear how he put himself through Columbia University as a rank-and-file Teamster; he wants to charm disenchanted employees, so we are informed that he is a family man, with a wife, four children and a relatively modest home in a Houston suburb. Such a lusterless mosaic of the private Lorenzo suggests that we aren’t missing much by being denied more intimate particulars.

More is known about the public man, but here, too, reality is obscured—by business-press hyperbole, Wall Street wish fulfillment and union propaganda. The Lorenzo legend—like his debt—has been rolled over for so many years that the myth now conceals history. The businessman we see is a caricature in black and white, a hard-charging, freewheeling, ruthlessly efficient apostle of economic Darwinism, but beneath the accretion of clichés is a gray, tentative figure who has never flourished in straight-up deregulated competition and has been kept aloft by the very courts and government agencies whose control of the aviation industry he has so often disparaged.

The opening chapter in any standard hagiography of Frank Lorenzo is the resurrect ion of Texas International Airlines. By the summer of 1986, after Lorenzo had commandeered Eastern, brought Continental out of bankruptcy and boosted Texas Air stock to $51.50 a share, Texas International had been canonized as his first certified miracle. And it is here that we begin our search for the man behind the myth. To understand how Lorenzo really works— and why his Texas Air empire doesn’t— requires a closer examination of the litany of Lorenzo miracles.

Francisco Anthony Lorenzo was born in Queens, New York, to parents who had emigrated from Spain as children. He received an MBA from Harvard in 1963 and put in a couple of years as a financial analyst for Trans World and Eastern airlines. In 1966 he and Bob Carney, a Harvard classmate, formed Lorenzo, Carney & Company, a consulting firm that matched Wall Street financiers with needy airlines. Three years later, they incorporated an aircraft-leasing business called Jet Capital, but by the time they were able to get the company up to speed in early 1971, two years of recession had dampened the aircraft-leasing outlook. The best investment opportunities in aviation turned out to be small regional airlines, which had suffered even more from the economic downturn than had the major trunk lines.

Jet Capital, flush with $1.5 million in cash raised through a public offering of common stock and warrants, made a run at Mohawk, a carrier based in Utica, New York, and failed. Then Chase Manhattan Bank, chief lender to Texas International, dropped that company into Jet Capital’s lap. The bank had summoned Lorenzo and Carney to Houston as $15,000-a-month consultants to come up with a plan to save the struggling carrier. Formerly Trans-Texas Airways, TI was based in Houston and had routes throughout the Southwest. Despite later, myth-building characterizations of pre-Lorenzo Texas International as a chewing-gum-and-baling-wire operation, what Lorenzo found when he looked it over was “basically a very good route structure, good people and good equipment.” In fact TI had done well enough in the 1960s to have committed the cardinal sin of airline management: overoptimistic expansion. With a fleet of 15 new DC-9s and a whopping debt service to match, the airline wasn’t prepared for the slump that settled over the industry from 1969 through 1971 and lost a total of close to $20 million.

Lorenzo and Carney’s solution took the form of an investment package whose main elements were classic Lorenzo: leverage and control. Building around Jet Capital’s $1.5 million in cash, they put together a $35 million equity-financing plan that would give Jet Capital 24 percent of Texas International’s stock and 58 percent of its voting power. The plan was approved by the shareholders, and in August 1972 Frank Lorenzo was elected president and chief executive of Texas International. He had virtually no experience in day-to-day airline management, but he had taken over at an unusually propitious time. The outlook for regional airlines had improved dramatically toward the end of 1971, and strong industry-wide gains would be registered throughout the rest of the decade. On top of that, in February 1971 the Civil Aeronautics Board voted to double the $24 million in annual subsidies it was paying nine regional airlines for their losses on unprofitable short-haul routes. Even as the profit outlook improved, the CAB continued to pay the vastly increased subsidies. By the time the agency decided to suspend Texas International’s payments after fiscal 1978, the airline, which had made a total of $20 million in net profits until then, had received about $50 million from the CAB. Almost half of Texas International’s return was due to the subsidies, according to the agency’s computations. Of course, those were the rules everyone played by under regulation, at least until the CAB began to encourage Lorenzo to break them—by discounting prices—at the same time that it was, in effect, paying him for playing fair.

Texas International earned modest profits in 1973-74, then weathered a three- month shutdown when ground and air crews struck in the winter of 1975. Since industry strike-aid payments kept the airline afloat at the break-even point, Lorenzo took advantage of the hiatus to prune unprofitable routes, trim his work force and move his debt balloon a few more years down the road. TI emerged from the labor strife stronger than ever, with three boom years for the industry and a burgeoning Sunbelt economy still ahead. The only cloud on this horizon was Southwest Airlines, an upstart intrastate commuter line founded in 1971. Regulated by the state of Texas instead of the CAB, Southwest could operate virtually like today’s deregulated airlines, setting its fares and selecting its routes without waiting for the board’s approval.

Texas International got enough action to turn a $3.2 million profit in 1976, but it still needed a competitive edge against Southwest, which was using its low fares and exclusive landing rights at Dallas’s close-in Love Field to lock up the lucrative Dallas-to-Houston route. Lorenzo turned to his benefactor, the Civil Aeronautics Board, and asked for permission to reduce fares by 50 percent on certain low-density flights to 11 cities. If he couldn’t undercut Southwest in Dallas and Houston, perhaps he could undercut his regulated competition on interstate routes. As it turned out, Lorenzo’s request, which threatened the very foundations of the carefully constructed edifice of airline regulation, was exactly what the CAB wanted to hear.

John Robson took over as head of the CAB in 1975 with the singular objective of putting the regulatory agency onto a self- destruct heading that would culminate in a free-market airline industry. He and his young staff believed with almost evangelic al fervor in the elasticity of the air-travel market: Lower fares brought about by free-market competition would release a stampede of consumers who had previously found flying prohibitively expensive. The vast new market would fill empty seats, and the industry would rake in higher profits in spite of reduced per-passenger revenues. When Lorenzo appeared with his request for discounted fares, the elasticity theory suddenly had its first test case. He got approval in less than two months.

Texas International marketed its new discount rates as “peanuts fares,” and the success of the pricing strategy seemed immediately to confirm the deregulationists’ forecasts. One flight between Albuquerque and Los Angeles, only 30 percent full at $76 dollars a ticket, filled 90 percent of its seats at half fare, lifting revenues on the flight by 75 percent. Within months the Civil Aeronautics Board extended its permission for peanuts fares to additional markets. With a CAB subsidy in one hand and a CAB dispensation to explore the free market in the other, Lorenzo and Texa s International earned more than $20 million over the next two years.

The peanuts fares might have remained a footnote in aviation history had Lorenzo not announced, in the summer of 1978, that Texas International had bought 9.2 percent of the stock in National Airlines, a major trunk carrier based in Miami. Lorenzo’s airline wasn’t the first to covet National; Pan American World Airways, seeking domestic feeder routes for its international flights, had secretly approached National earlier in the year. But Lorenzo, who eventually acquired almost 25 percent of the company’s stock, was the first to openly declare his intentions and receive the accompanying publicity. Even when Pan American beat him out after a year of dickering with the CAB and National’s management, the brash Lorenzo came off like a winner for simply making the challenge. Texas International made a pretax profit of $46 million when it sold its shares in National to Pan American in the summer of 1979. Of TI’s impressive $41 million net income that year, less than $7 million was accounted for by actual profits from operations.

Although the CAB would not allow unrestricted entry to domestic routes until the end of 1981 and would not eliminate all price restrictions until January 1, 1983 (the agency terminated itself exactly two years later), its acquiescence on the National-Pan American merger signaled to America’s airlines that they had better begin preparing for the coming fury of free-market competition. There was considerable confusion, however, about what form the new airlines should take to compete effectively in the deregulated skies. Briefly in vogue was the “upstart” theory, which held that such small, never-regulated airlines as Southwest would quickly outmaneuver the lumbering, regulation-configured major trunk carriers. Lorenzo tested this thesis in 1980 by creating nonunion New York Air, which consistently lost money for the next six years as it tried to compete with Eastern’s New York-Washington shuttle.

More enduring was the countervailing “two airline” theory, which had been tossed about for years by the academicians at the CAB. In this world, the big would indeed get bigger, gradually gobbling up those airlines that could not obtain a competitive “critical mass.” The ultimate extrapolation would lead to an industry made up of two ultra-efficient leviathans going toe-to-toe, although an industry with five or six major carriers—the situation that exists today—would also validate the theory.

Lorenzo eventually opted to get big. In September 1979 he had as much as $100 million in cash from the sale of National’s stock and the issue of more than $50 million worth of equipment-trust certificates secured by Texas International’s aircraft. Eager to use his purchasing power, he invited Trans World Airline’s chairman, Edwin Smart, to breakfast at the Hotel Carlyle in New York and offered to buy TWA, which was 10 times the size of Texas International. The enraged Smart stalked out without eating. Lorenzo was undeterred by the rebuke; he knew there were plenty of airlines to choose from.

Texas Air Corporation, which was formed in June 1980 as a holding company for Texas International and New York Air, purchased a 9.5 percent interest in the stock of Continental Airlines, the nation’s 10th largest carrier, in early 1981 and announced that it intended to make an offer for a controlling interest. The takeover was complicated by the attempts of Continental’s employees to buy the company. (Lorenzo’s establishment of nonunion New York Air had been a red flag for airline workers.) The drama reached a tragic pitch with the suicide of Continental’s dispirited president, Alvin L. Feldman, in August 1981.

At the time many observers wondered why Lorenzo wanted an airline that had lost $55 million in the preceding 18 months, but his two extant carriers were going nowhere—Texas International lost $34 million in 1981—and he needed to make a move. Continental, even with its losses, was a “premier service” airline (Chivas Regal scotch was served in economy class) with a good reputation among business travelers, a market that TI, with its leisure-oriented route structure and sloppy service, had never been able to tap. If there was any kind of industry-wide upturn, Texas Air could combine the two airlines into a profitable critical mass.

It was not to be. Although the major airlines struggled in 1981 and 1982, most were able to contain their losses in the latter year and build on a strong upward surge in 1983 to record profits in 1984. For Texas Air, on the other hand, the situation went from bad to worse. Texas International was merged into Continental in 1982, and the new team generated more than $100 million in operating losses.

Lorenzo, not without cause, blamed high labor costs for his difficulties. Flight attendants—who were averaging $39,000 a year in wages and benefits—and pilots offered $80 million in concessions, but Lorenzo wanted more and set a September 19 deadline for an agreement on an additional $150 million from the workers. It wasn’t an environment that encouraged a lot of self-sacrifice. A number of Lorenzo’s new management elite were the same young ex-CAB staff members who had formulated deregulation theory, and they had little patience with real world impediments to their sophisticated ideology. Five days after his ultimatum, Lorenzo announced that the airline was filing for reorganization under Chapter 11 of the federal bankruptcy law.

The Chapter 11 filing was a huge success. Lorenzo fired all 12,000 employees, then invited 4,000 back at anywhere from 40 percent to 60 percent of their previous wages. With both the airline industry and the economy still struggling, most of them returned. When the Airline Pilots Association struck the airline a few days later, many pilots crossed the picket lines and eventually voted to forgo representation by the union altogether. Within three days of the filing, Lorenzo’s scaled-down “New Continental” was flying again, offering $49 fares for any nonstop domestic flight.

It appeared that Lorenzo had created a formidable deregulation flying machine. Since labor costs had been cut by more than $250 million a year and were now the lowest in the industry, Continental could offer lower fares than any of its major trunk competitors, most of whom cut back on their schedules after growing weary of trying to match the discounted fares. Continental’s flights were so glutted that the bankrupt airline had to order dozens of new jets.

The new Continental flew under Chapter 11 for three weeks short of three years and earned more than $150 million in total profits during that period. When the carrier emerged from bankruptcy, it was operating a fleet of 147 aircraft versus 105 three years earlier. Here was conclusive proof of market elasticity. Unfortunately, there was a billion-dollar glitch in the equation— exactly the amount of the interest payments and long-term debt maturities that had been deferred while Continental financed upward of a billion dollars’ worth of new planes. As long as it was protected from its creditors, the airline could make money. If it had been obligated to service its debts, it would have been a major loser during a period when the rest of the industry showed record profits. Nevertheless, Continental’s emergence from Chapter 11 was widely hailed as another Lorenzo miracle.

Since it was clear to anyone who could read the balance sheets that Continental wasn’t competitive outside the bubble of Chapter 11, Lorenzo began working to build a “mega-carrier,” to use his own term, well before the airline emerged from bankruptcy. In the summer of 1985, Texas Air made another bid for TWA. Again unions played a critical role in Lorenzo’s negotiations, this time by siding with Carl Icahn, who wound up with the company. Unfazed as usual, Lorenzo turned his sights on the only airline whose unions so despised their own president that they would actually prefer Frank Lorenzo: Eastern and Frank Borman. In February 1986, Texas Air nailed down a $640- million deal to acquire Eastern, its fleet of 300 aircraft, and its System One computer reservation operation—a crucial tool for deregulation-era fare juggling. The price was generally regarded as a steal; Eastern’s cash balance of $463 million was more than Texas Air’s cash outlay. But Eastern was also heavily in debt, with more than $3 billion in obligations. (Its alarming 87 percent debt-to-equity ratio was still less than Continental’s post-bankruptcy 95 percent.) In the week following the deal, Texas Air stock climbed from $17 to $28 a share.

The acquisition of Eastern did not help Continental gain critical mass after all, because to merge the two airlines would permit Eastern’s unions to bargain for Continental’s nonunion employees. So Lorenzo still needed an ideal mate for Continental, and he found it in People Express, the nonunion, employee-owned discount airline founded by Donald Burr, a former Lorenzo lieutenant. The airline had been battered into bankruptcy by Chapter 11- assisted Continental. In September 1986, Burr grudgingly accepted Lorenzo’s offer for People Express and its subsidiary, Frontier Airlines. Texas Air picked up 110 planes, about 1,000 nonunion pilots and $750 million more in long-term debt.

After absorbing People Express and Frontier, Continental, with its fleet of 352 planes, became a bona fide mega-carrier. The overall Texas Air strategy was for Continental, with its low nonunion costs, to drive company earnings while Lorenzo attacked Eastern’s high labor bill. Eastern’s unions were a notoriously tough bunch, but Texas Air’s management felt they could be tamed by the threat of transferring Eastern’s planes, routes and jobs to Continental, whose success would be the big stick against Eastern’s unions.

The plan immediately went awry. Texas Air had formulated virtually no plans for the merger of “cheap frills” Continental and “no-frills” People and was surprised to find that many of its new employees were unable to handle jetways or operate reservations and ticketing computers. Behind the scenes, planes went wanting for spare parts, and the 13 different types of aircraft now operated by Continental made a farce of the standardization procedures necessary for mega-carrier efficiency. Texas Air exacerbated the inherent problems by frantically shifting managerial personnel in the midst of the crisis. Employee morale, which had remained relatively high through the Chapter 11 period, now plummeted, and Continental’s pilots began to leave at twice the normal industry rate, adding to the work load of the remaining aircrews. The Department of Transportation collected record numbers of consumer complaints, and the airline lost $40 million in the first quarter of 1987 on the way to dropping $258 million for the year. Eastern, by contrast, showed a second-quarter profit of $27 million.

Confronted with the collapse of its origin al strategy for bringing Eastern’s unions in line, Texas Air embarked on a plan designed to increase Eastern’s liquidity in the event of a strike by members of the International Association of Machinists, whose contract expired last December 31. Eastern’s unions countered that Lorenzo was deliberately dismantling the airline. Whatever the intent, Texas Air took the computer reservation system off Eastern’s hands for a $100 million note at 6.5 percent, sold 20 aircraft, put an additional 21 on the market and drew more than $100 million in cash out of Eastern through a variety of questionable transactions, including a “strike readiness” fee of $22.5 million paid to Continental and the inexplicable sale of $25 million worth of unsecured notes in bankrupt People Express to Eastern. The boldest stroke was the proposed acquisition by Texas Air of Eastern’s venerable Washington-New York- Boston shuttles—believed to account for one-third of the airline’s total operating profits—for $225 million. After a court fight with the unions and awaiting arbitration of Eastern’s labor problems, Lorenzo backed away from the shuttle deal shortly after the DOT report was released.

Continental, meanwhile, continued to underperform even the stripped-down Eastern, losing a stunning $80 million in the first quarter of this year compared with $64.5 million at Eastern. The Transportation Department’s auditors found that Texas Air’s own revised cash-flow projections for Continental would be “substantially less than anticipated,” while Eastern’s would be higher. But amid all the smoke at the Eastern front, few people bothered to ask the salient question about Frank Lorenzo’s air empire: Why can’t Continental make money? The ultimate deregulation flying machine Lorenzo says he could build at Eastern—if only his unions would play fair—already exists, and it isn’t getting airborne.

Continental’s problems start at the top, in a Byzantine corporate structure that offers Lorenzo and Texas Air’s managers control without responsibility. The leverage situation is one of the wonders of modern finance: The tiny Jet Capital, privately held by a handful of shareholders, with Lorenzo controlling a slight majority, owns just 3 percent of the equity in Texas Air but, through a special class of stock, maintains 34 percent voting control and the right to elect seven of Texas Air’s 11 directors. Texas Air in turn manages more than 20 subsidiary corporations, ranging from Texas Air Fuel Management Inc., which sells fuel to all of Lorenzo’s airlines, to Continental Airlines Inc. with its collection of small feeder airlines and the corporate vestiges of the companies it has absorbed. (Texas International, New York Air, People Express and Frontier no longer exist as independent carriers.)

Texas Air is not a particularly doting parent. While the corporation likes to arrange the financing for its subsidiaries, it prefers that they guarantee and service most of the debt acquired for them. As a consequence, Texas Air’s own corporate debt service will run to only $82 million this year. The parent company has been accused by its unions of “upstreaming” cash in the form of management and service fees charged its subsidiaries. Some of the accusations, despite Transportation Department waffling on the question, seem justified. Texas Air Fuel Management purports to offer Texas Air’s carriers the benefit of large-volume fuel purchases, but Continental and Eastern have been charged more in fees than they save by buying their fuel from Texas Air Fuel.

Undisciplined management also keeps Texas Air from achieving the operational efficiencies supposedly available to a mega-carrier. Lorenzo has in the past boasted about his “eclectic” style of management and the freedom he offers his lieutenants to set their own hours and make their own decisions. But airlines, which require intense day-to-day supervision to eke out the extremely marginal ret urns on their enormous revenues, are probably not the best place for free-spirited executives. Texas Air may have too much managerial entrepreneurship for a business that is fundamentally very conservative, whatever notions one may have about the romance of flight.

Nonunion Continental also suffers from too little labor entrepreneurship. While low wages have enabled the airline to halve its labor costs compared with some of the other mega-carriers, a dispirited work force can exact a severe economic penalty in the airline business, and not simply because harried flight attendants and grouchy ticket agents are the worst form of consumer relations. “Pilots think of themselves as management,” says George Hopkins, a professor of history at Western Illinois University and author of a book about the Airline Pilots Association published by Harvard University Press. “They routinely perform such management functions as deciding which approach path will save the most fuel.” The same can be said of mechanics, who regularly make independent judgments that can add up to enormous profit or loss margins in the micro-managed economy of daily airline operations. No upper- or mid- level management team, no matter how creative their cost cutting, can overcome the cost disadvantage of on-line employees who feel little allegiance to the company they work for. Lorenzo’s jugular attacks on labor may have been penny-wise and pound-foolish.

The real failing at Continental has been a flawed long-term strategy. Executives have paid periodic lip service to recapturing the business travelers turned off by the airline’s poor service and low reliability. Yet every time Continental finds itself in a competitive situation, the reflexive response is to beat the competition on price, not performance, and hope that market elasticity will fill seats with discretionary passengers who otherwise might not have flown on any airline. In the high-flying days of 1986, Philip Bakes, president of Eastern, blithely referred to airline service as “a commodity. We’re trying to build some value into it. But no matter what you do, brand loyalty will decline, and price and frequency will be the dominating forces.” In the midst of Continental’s massive merger woes in early 1987, the airline introduced its Max$aver fares, a full 40 percent lower than its competitors’ “supersaver” fares, and the marketplace quickly exposed the limits of elasticity. Traffic did not increase enough to offset the revenue losses.

The marketplace has also assailed the deregulationists’ predictions about the importance of service and image to air- travel consumers. The two most profitable airlines throughout the deregulation era have been American and Delta, both of which have relatively high labor costs and are perennial winners in customer satisfaction. American is so confident that passengers will pay extra for superior service that last fall it began to experiment with “two-tier” pricing at the discount end, offering higher fares than its competitors. As for brand loyalty, when Delta was plagued by a string of in-flight mishaps last year, there was not even a short-term decline in its bookings.

For all its problems, Lorenzo’s air empire may still be saved, probably through continued sales of Eastern’s assets (or perhaps what is left of the whole company, although its marketability is questionable without the computer reservation system) and, more important, the connivance of deregulation’s ultimate irony: a deregulate d market that is starting to look very much like the regulated market. Many major “hub” cities are now dominated by one or two mega-carriers, and the limited number of gates and landing slots—publicly financed facilities that the airlines are now permitted to own and dispose of as private property—precludes the entry of new competitors. Many experts believe that a new era of oligopoly pricing is already at hand, and the rising fares may save Lorenzo from his deregulationist pricing orthodoxy. But even to compete in such a cosseting environment, Lorenzo will have to stop whining about labor, get his managerial house in order, and formulate a pragmatic long-term strategy to make a winner out of Continental, the airline that deregulation built. If the real Frank Lorenzo, who has performed few of the prodigies attributed to his mythical alter ego, can make Continental fly, he will have performed his first real miracle.

One comment

Do you want to comment?

Comments RSS and TrackBack URI

Trackbacks