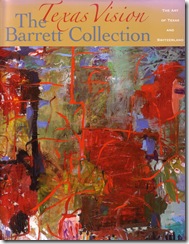

Excerpted from Texas Vision: The Barrett Collection, published by SMU Press/The Meadows Museum

Author’s note:

Texas Vision was written in 1992 as the catalog essay for an unprecedented historical survey of Texas art: an exhibition of the Barrett Collection intended to tour Europe and, we hoped, triumphantly return home to similarly open the eyes of Texas museum-goers – a sort of back door approach to getting Texas art in front of Texas audiences. But the notion that Texas has a rich cultural history is no easier to sell abroad than it is at home, and what would have been a landmark exhibition never materialized. Richard and Nona Barrett, however, were sufficiently ahead of their time that neither Texas collectors nor Texas museums, while considerably more interested in Texas art they were twelve years ago (due in great part to the Barretts’ own tireless proselytizing), have yet to catch up to them. Thanks to the enlightened efforts of Ted Pillsbury and the Meadows Museum, the Barrett Collection at last comes to a Texas audience (through the front door, at that), and its unique vision of Texas’ culture and history remains as revelatory today as it was when this essay was written.

Michael Ennis

TEXAS VISION: THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS OF HISTORY

I first saw the Barrett collection in the fall of 1989. I had been invited to Nona and Richard Barrett’s Dallas home on a social occasion, and although I had heard that the Barretts were energetically collecting the work of Texas artists, I was more skeptical than expectant. Not that I had summarily dismissed the notion of the Barretts as serious collectors. I had simply given up on the notion that any Texans would ever become serious collectors of Texas art.

This was not, from my perspective, an unreasonable prejudice. Since 1977, I had regularly written about art for Texas Monthly magazine, and during that tenure I had witnessed an evolution so dramatic that it might be more properly called a revolution. In 1977 Houston had emerged as the hotbed of Texas art, but no temperate observer would have dared to suggest that the city was on the verge of becoming an established "regional" center like Los Angeles or Chicago. The Houston Contemporary Arts Museum under James Harithas was zealously exhibiting the work of Texas artists, but too often the talent wasn’t equal to the exposure (a situation that would be reversed in the 1980’s). The inclusion of a Texas artist in a national exhibition such as the Whitney Biennial was infrequent enough to represent the pinnacle of ambition for a Texas artist determined to stay at home. Those with higher aspirations (or more persistent delusions) moved to New York, following a time-honored tradition epitomized by Robert Rauschenberg, who bid his native state farewell in 1945.

A little more than a decade later, in 1988, I saw a very fine exhibition called the "First Texas Triennial," organized by Houston’s Contemporary Arts Museum as a showcase for relatively unexposed Texas artists. (A number of the artists present here in Texas Vision – Tracy Harris, Bill Komodore, Celia Munoz, Brian Portman, Randy Twaddle, Michael Whitehead – were represented in the Triennial, so I will place their work into evidence as to the overall quality of the exhibit.) As I looked over the biographies of the artists included in the Triennial, I was struck by a certain pattern. Only four of the twenty-four artists were Texas natives, and the majority (14) had been educated outside of Texas. A typical example is Brian Portman, who was born in Rhode Island in 1960, earned his BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design, and came to Texas in 1983 as a Core Fellow, a corporate-sponsored residency at the Glassel School of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. Portman’s exhibition history also revealed a pattern that had become typical: first the Core Fellows exhibition; then group shows at DiverseWorks, a Houston alternative space; and on to commercial galleries in Dallas (Barry Whistler Gallery) and Houston (Hiram Butler Gallery).

The Triennial biographies illustrated a striking reversal of Texas’ historic propensity to export its raw talent. Not only were the University of Houston MFA’s staying home, but talented young artists from all over the world were coming to Houston to build their careers, attracted by a sophisticated and successful support system. Over the past two decades the University of Houston has built one of the nation’s most prestigious undergraduate and graduate art programs; in 1979 the University also began sponsoring Texas’ first alternative space, The Lawndale Art & Performance Center, which is still in operation. DiverseWorks, founded in 1982, has earned a nationwide reputation for its professionalism and aggressive innovation, and has debuted the work of a number of Texas’ most promising young artists. During the 1980’s, a small group of galleries dedicated to Texas art became commercially viable despite the celebrated Texas oil bust, a much more severe and prolonged downturn than the recession that afflicted the rest of the United States in the early 1990’s; Texas’ best young artists can now reasonably expect to make a living from sales out of a Dallas or Houston gallery. Although Texas museums were slow to recognize the ascendence of Texas art, today the array of public venues for contemporary art in Houston stands comparison with that in any American city: In addition to the Contemporary Arts Museum and the Blaffer Gallery of the University of Houston, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts also shows Texas art with some regularity and insight (most notably the landmark 1984 exhibition "Fresh Paint: the Houston School", which marked the coming-of-age of Houston art), as does the privately-funded Menil Museum, capital of the de Menil family’s far-flung collecting empire.

Somehow the Texas art boom escaped the notice of Texas art collectors. During the oil boom of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, Texans bought art with a furious disregard for price or quality. While one might assume that Texas petro-dollars were squandered on Remington bronzes and Taos desertscapes, in fact they were lavished on contemporary art, most particularly color- field painting of the high-Greenbergian persuasion. New York galleries quickly discovered that Texans were unusually receptive to the work of fading luminaries in whom New York collectors were no longer interested. The New York school, limping into history, had its last stand in Houston and Dallas.

None of this spending trickled down to local talent. The trailblazing Texas gallery of the 1980’s, Graham Gallery, had its genesis in a converted garage, and became successful enough to move into more conventional quarters – and eventually to support a number of its artists – only because owner William Graham realized that the key to survival was finding out-of-state buyers for Texas art. When the oil boom went bust in the mid-1980’s, the dim prospect of interesting Texas collectors in Texas art disappeared entirely. Texas galleries, artists, and arts organizations persisted and in many cases thrived throughout the bust simply because they had already learned to do without the support of the Texas economy.

It was with this history in mind that I entered Nona and Richard Barrett’s home on that October night in 1989. The house itself in no way advertised the Barretts passion for contemporary art; it is comfortable but not palatial, in an updated Georgian style, with traditional furnishings. The art one notices on entering is small-scale, hung in odd places in a relatively modest foyer that immediately accesses a large stairwell. Several of the pieces in the foyer were engaging, but they communicated little of the ambition and bravado of contemporary Texas art.

So, with unrelieved skepticism, I began to climb the stairs. The stairs turned and I could see into an expansive landing that encompassed the stairwell, offering as much wall space as a Soho gallery. The pictures were crowded as they had been in the foyer, but these were immense canvasses, full-scale, full-tilt paintings by Derek Boshier, Bill Komodore, Richard Thompson, Michael Whitehead, Melissa Miller. The energy was palpable: in bold, painterly gestures and daring compositional fiats, in a sense of fierce intellectual independence. Instead of the aimless, image-appropriating prattle of so much postmodern art, here was the uncompromisingly direct symbolic language of Texas postmodernism.

I was astonished. The Barretts weren’t politely dabbling in Texas art, they were collecting it with the same irrepressible passion that had produced it. After years of looking at the predictable, brand-name late modern and postmodern art displayed in the homes of affluent Texans as a badge of sophistication, I found the vision of a similarly well-endowed collection dedicated to Texas art simply breathtaking.

The second time I saw the Barrett collection, in the summer of 1991, was another revelation. Even a glance revealed that the Barretts had been very busy in the intervening two years. They had added literally hundreds of works, but even more arresting than the quantity and quality of the new additions was the sense of direction now apparent in the collection as a whole. I was particularly drawn to the works dating from the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, and found myself making connections between these pieces and the Texas art of the 1980’s. The Barretts, I suddenly realized, were more than just adventuresome connoisseurs; they were collecting Texas art with the goal of providing it a history. And in this they had charged headlong into terra incognita.

The historiography of Texas art can be measured with a few handfuls: a handful of diligent monographs, a scant handful of exhibitions and catalogues devoted to various episodes in the history of Texas art. There is no comprehensive work on Texas art; there has never been an exhibition offering more than a cursory overview of Texas art from the 19th century to the present. The Dallas Museum of Art, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and the San Antonio Museum Association all own extensive collections of Texas art, acquired fitfully over many decades. But with the exception of recent low-profile, temporary exhibits by all three museums (only the San Antonio exhibition featured a catalogue [published after exhib – not out yet]), these collections have remained hidden from the public and virtually untouched by interpretive scholarship.

Constructing a history of Texas art from these meagre resources is difficult enough, but the task is made considerably more onerous by the peculiar institution that is Texas history. In this case the problem isn’t a lack of attention to the subject, but a surfeit. Texas’s unique saga, its stirring fight for independence from Mexico and its short-lived republic, its cattle kingdoms and oil booms, has been mined by historians even more industriously than it has by the popular media. But most of this material, even the most venerated scholarship, is highly suspect, too often dedicated to preserving a mythic realm rather than portraying the Texas of fact and record.

At this point it is necessary to ask the question: Is there really any need to establish a relationship between Texas art and Texas history? One currently fashionable critical posture is to reject the idea of a Texas art that has any defining regional characteristics, and to consider it solely in an art-historical context; this opinion meshes rather neatly with that of a huge constituency of know-nothings – among them many Texas historians – who find in Texas art only an alien cosmopolitanism that can never reveal the essential Texas. Something of a middle ground is taken by critics who hold that Texas art has a reckless factural exuberance and uncomplicated emotional candor that betrays a distinctly Texan character, even if the imagery and themes provide little evidence of Texas origins. Of course, this sort of speculation is just another incarnation of the question that bedeviled American artists earlier in this century: is there such a thing as American art, and if so, what is American about it? Today, when "Texas" is substituted for "American," the range of answers seems to be from "no" to "yes, but…"

However, I intend to argue – quite unfashionably – that the answer to the question "is there such a thing as Texas art?" is an emphatic "yes." What is Texan about it is not as simple as an affinity for bold strokes, whether emotional or literal. It is a pervading sense of place, a fundamental Texan-ness most directly evidenced in a strong tradition of narrative and landscape art, but which also emerges through a more subtle appropriation of the same language in which so much of Texas’ history has been written: the language of myth. Perhaps the mythic images we see in Texas Vision do not resemble the historians’ vision of Texas, but that is not to say that these images are not exceptionally faithful to their Texas sources. I believe that the Barrett collection represents an authentic vision of Texas: sharp, precise, often complex, but always illuminating, a vision much more profound and consequential than the caricature created by Texas historians. In Texas art we find a window into the soul of Texas and, ultimately, an insight into a singularly American state of mind.

Which brings us to the real problem in reconciling Texas art and Texas history. To fully encompass the Texas vision revealed in this exhibition would require re-writing the history of Texas, and then proceeding with a comprehensive history of Texas art. Scholars have just begun the former endeavor, while the latter remains well beyond the horizon – and is certainly beyond the reach of this essay. We can, however, at least try to discern some features of that distant landscape. To that end, I offer a series of fragmentary views – snapshots, if you will – of Texas history and Texas art, each separated by a half century: 1836, 1886, 1936, and 1986.

1836: AFTER THE FALL

Before dawn on March 6, 1836, 1500 assault troops commanded by the Mexican dictator Antonio Lopes de Santa Anna stormed the walls of the San Antonio de Valero mission, better known as the Alamo, slaughtering the 183 defenders almost to the last man; significantly, a slave in the possession of William Barret Travis, commander of the Texas garrison, was spared. Less than three weeks later, the citizens of Nacogdoches, then one of Texas’ largest towns, issued a proclamation reading in part: "They died martyrs to liberty; and on the altar of their sacrifice will be made many a vow that shall break the shackles of tyranny. Thermopylae is no longer without parallel, and when time shall consecrate the dead of the Alamo, Travis and his companions will named in rivalry with Leonidas and his Spartan band."

That the 182 Texas martyrs were avenged at the Battle of San Jacinto within weeks of the fall of the Alamo has the predictability of a motion-picture script – and, of course, has inspired more than a few. More surprising is to realize that Texans living in 1836 so quickly perceived that they were attending the birth of a myth, that they understood that their turbulent present had the dimensions of a sacred history. Rarely has heat-of-the-moment hyperbole proved so durable; with the Alamo as its apotheosis, this sacred history, accreted in subsequent generations with heroic sagas of Texas Rangers, Cowboys, Cattle Barons, Gunslingers, Wildcatters, and Wheeler- Dealers, has dominated most Texans’ – and most outsiders’- perceptions of the state. Originally a variation on the American frontier myth, over the years the Texas myth has become a superset of that fundamental American belief in unlimited horizons and unfettered individualism. The defenders of the Alamo have become the quintessential American heroes, their last stand an indelible American icon [il. The Fall of the Alamo by Robert Jenkins Onderdonk (San Antonio Museum Association)], and their heirs have seemingly evolved into a race of "Super- Americans" (the title of a 1961 book on Texas by New Yorker writer John Bainbridge) whose unbroken frontier spirit is resented, envied, and emulated by Americans from Hawaii to Maine.

The Texas myth is more than just a colorful cultural patrimony. It is a dynamic force in Texas society today, a natural resource and export commodity as important to the state’s past and future as oil. At the least it provides a cultural point of reference for one of the most geographically and ethnically diverse political entities in the world, a nation- state larger than France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland combined, in which 40 percent of the population is a racial or ethnic minority. "Texas isn’t a state, it’s a state of mind," the cliche goes, but Texas is actually a remarkably variegated meeting of the minds, a place of historic collisions: between native Americans and immigrant Americans; between the Old South and the New West; between the Anglo-Protestant culture of north America and the Hispanic-Roman Catholic culture of Latin America; between the timeless, third-world poverty of border "colonias" and the twenty-first century promise of glittering "edge cities" rising from the "silicon prairie." Texas is a place so polymorphic, so culturally fractured, that only its abiding myth seems to hold it together.

The power of that myth is attested by its global reach and consequences. As Lyndon Johnson escalated American involvement in Viet Nam, he invoked the tradition of the Alamo so frequently that the New York Times editorially chastised: "If Americans must remember the Alamo, let’s remember that gallant men died needlessly in that old mission… To persevere in folly is no virtue." But a generation later most Americans still want to believe. The 1992 Presidential campaign – and perhaps the landscape of American politics – was irrevocably altered by the dust-up between a nominal Texan and a real one: Tough-talking incumbent George Bush, a New Englander who invented his own personal myth about his days in the Texas oil business, steadfastly maintained his residence-of-record in a Houston hotel even when the hotel went bankrupt; plain-speaking Texas billionaire Ross Perot stepped forward as the self- proclaimed "sheriff" determined to rid the nation of outlaw politicians. Bill Clinton won the election, but collectively, the two Texans won the popular vote.

The high priests of the sacred history of Texas have traditionally been the state’s historians, who have jealously guarded their myth against revisionists, and where necessary, the facts. Beginning with George P. Garrison at the turn of the century, the most respected Texas historians – Charles W. Ramsdell, Eugene C. Barker, and Walter Prescott Webb – have successively assumed the role of defender of the faith, writing histories in which Anglo-Protestant Texans, armed with unflagging courage and incorruptible virtue, prove their invincibility in the social Darwinist arena of frontier conquest. The preservation of this myth is still viewed as a moral imperative among most Texas historians and writers, as evidenced in this excerpt from a 1986 essay titled "Texas Mythology: Now and Forever," by T. R. Fehrenbach, author of Lone Star, the all-time best-selling history of Texas (and a source frequently cited by writers who imagine themselves in the myth-puncturing business, such as Lyndon Johnson biographer Robert Caro.):

The most interesting fact about Texas society today is that it works. It may not be the most equitable or intelligent, the most developed or the most artistic or the kindest, but, like the society of Singapore, for the present it works. Its denizens believe in it; they have confidence in both the past and present. A sense of common past makes it easier to believe in a common future…

The last thing I would want us to do with the Texas history-mythology is to de-mythologize it.

There is, however, a creeping heresy among the lesser clergy; within the past twenty years, a small contingent of maverick scholars has indeed begun to de-mythologize Texas history. Very little of their work has found a popular forum, but occasionally a leaf or two of the growing revisionist corpus drifts into the public eye and provokes a furor. In the 1970’s, the disclosure of reliable eyewitness evidence, originally published in Mexico in 1836, that Davey Crockett surrendered and was executed following the battle of the Alamo was greeted with howling denunciations by the local and national press – which cited the movie versions of Crockett’s death as the incontestable primary source. The mass-media orthodoxy has since been sustained by novelist James Michener in his sprawling epic Texas (1987), who considered the revisionist evidence and dismissed it with a firm "Unlikely, that."

Given the vehement reaction to a rather mild rescripting of Crockett’s exit (the eyewitness, a Mexican staff officer, reported that Crockett met his torture and execution heroically), it isn’t surprising that far more substantial redactions of the Texas myth have failed to engage a wider audience. The Texas myth is essentially a creation myth, and disabusing true-believers of their interpretation of Genesis is always a risky business.

Like the universe of Genesis, Texas at the moment of its creation was a dark void, a vast, unsettled land, neglected for two-and-a-half centuries by a Spanish empire for which Texas merely served as a buffer against French New World ambitions. Across this darkness – so the myth tells us – had moved the light of Anglo-American civilization, transforming the Hispanic, Roman Catholic wasteland into a English-speaking, Protestant garden. In 1820, the year that Spanish authorities opened Texas to colonization, only 3,000 mostly Hispanic settlers inhabited a strip of woodlands and black-soil prairie along the eastern third of the state. By 1836, 30,000 Americans, most of whom were immigrants from the southern United States, had settled in the same rough crescent of Texas land.

Stephen F. Austin, hallowed as the Father of Texas, was the most important of the empresarios extended grants by the Mexican government (Mexico had won independence from Spain in 1821 and renewed many of the Spanish grants) to bring settlers into Texas. Austin, whose colony contributed a third of Texas’ population in 1836, saw the process of settlement as one of redemption, the creation of "the garden of North America" out of a wilderness through the virtuous application and self-sacrifice of his colonists. "My object, the sole and only desire of my ambition since I first saw Texas, was to redeem it from the wilderness, to settle it with intelligent, honorable, and enterprising people," Austin wrote in 1830. Conquered by "the axe, the plough, and the hoe," Austin’s Texas would become "a second Eden."

According to the myth, the snake in Austin’s garden was the Mexican central government under Santa Anna, who had wrested power from the liberal constitutional government in 1834; until then, Texans had been content to press for full statehood under the Mexican federal constitution of 1824 (prior to the revolution, Texas was part of the state of Texas y Coahuila, with its capital in northern Mexico.) Santa Anna adopted a policy of intimidation against the Texans, sending troops to enforce the collection of customs duties. The crackdown quickly radicalized the statehood movement into an independence movement, and full- scale war became inevitable. Of course, virtue and love of freedom prevailed, and the snake was driven from the garden.

In truth, the snake in the garden of Texas wasn’t Mexican despotism, but rather the American institution of slavery. The Mexican revolutionaries who fought to free their country from Spain were strongly disposed to abolition, although there were relatively few slaves in New Spain; only with the mushrooming development of Texas by slave-owning immigrants from the southern United States did the issue become pressing for Mexican lawmakers. In 1827, the state constitution of Coahuila y Texas restricted slavery by prohibiting further importation of slaves and emancipating at birth any child born to a slave; Texas settlers quickly learned to circumvent the first restriction by nominally freeing their slaves before entering Texas, then forcing them to sign life-time employment contracts at a subsistence wage.

Austin reflected the attitude of many Texans on the issue. He acknowledged that the institution of slavery was an "evil." But he personally owned slaves, and he considered slave labor essential to the rapid settlement of Texas. Austin was particularly concerned that abolition would discourage the better class of settler he sought. In 1825 he wrote the governor of Coahuila y Texas that without slavery, Texas "cannot expect colonists with large and competent means, nor can we have hands for the cultivation of Cotton or Sugar, and consequently these fertile lands, instead of being occupied by wealthy planters, will remain for many years in the hands of mere shepherds, or poor people…"

The Mexican government initially concurred with Austin’s it’s-good-for-business argument, exempting Texas from an 1829 general emancipation decree in order to maintain the pace of economic growth. But a year later, Mexican policy-makers, suddenly alarmed at the increasingly assertive American presence in their buffer zone, prohibited further immigration into Texas. As an additional deterrent to Anglo settlers, the new law banned the importation of slaves, and limited contracts of servitude to ten years.

With the outbreak of war, legal maneuvering gave way to impassioned rhetoric from both sides. As Santa Anna marched on the Alamo, he wrote back to Mexico City: "Shall we permit those wretches [slaves] to moan in chains any longer in a country whose kind laws protect the liberty of man without distinction of caste or color?" Texas revolutionary leader William H. Wharton, who had chaired an 1833 convention of Texas settlers, in turn protested, "With a sickly philanthropy worthy of the abolitionists of these United States, they [the Mexicans] have… intermeddled with our slave population, and have even impotently threatened… to emancipate them…"

So strongly was the Texas cause identified with the advancement of slavery that when the Texas victory at San Jacinto was announced in Washington in May 1836, Massachusetts congressman John Quincy Adams railed before the House that the Texas victory represented "the reestablishment of slavery in territory where it had already been abolished by Mexican law." For the next ten years anti-slavery forces in the United States Congress would block the single policy objective of the struggling, destitute Republic of Texas: to be annexed by the United States. The opposition to annexation was bolstered by the publication in 1837 of a book by abolitionist Benjamin Lundy, who had traveled in Texas for several years just prior to the revolution; Lundy’s tome was titled The War in Texas: A Review of Facts… Showing that This Contest is a Crusade… to Reestablish, Extend, and Perpetuate the System of Slavery and the Slave Trade.

Whether the defense of slavery was the primary motive or a secondary cause of the "Texian" fight for freedom is subject to debate even among revisionists. But the facts leave little to dispute about the effects of the Texas victory. "All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas… shall remain in a like state of servitude…" declared the constitution of the Republic of Texas in 1836. "No free person of African descent, either in whole or in part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the republic…"

With this unambiguous endorsement, an army of slaveholders advanced on Texas in the decades following the revolution. In 1836, the slave population of Texas was roughly 3000 – about one tenth of the total. By the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the white population of Texas had grown fourteen-fold to 420,000, while the slave population had increased almost fifty times, to 170,000. Cotton, the most profitable cash crop, was king in Texas’ antebellum boom, and slaveholders held almost three-quarters of all wealth in pre-Civil War Texas. As Randolph B. Campbell concludes in his landmark 1989 study An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, "Slaveholders dominated the the state’s economy, controlled its politics, and occupied the top rung on the social ladder… In short, the Peculiar Institution influenced and shaped virtually every aspect of life in the Lone Star state."

That Texas’ freedom-fighter founding fathers were constructing a slaveholding empire at a time when most of the world was dismantling the institution of human bondage is evidently a matter of some embarrassment to Texas historians, who have chosen to emphasize Texas’ western character rather than its profoundly southern sources; one doesn’t find the Cotton Planter on the roster of archetypal Texas heroes. Seminal Texas historians George P. Garrison (writing in 1906) and Eugene C. Barker (writing in 1924) dismissed the connection between slavery and the Texas revolution with bizarre logic: Taking literally the accusations of a "conspiracy of the slavocracy" hurled by nineteenth century abolitionist firebrands like Lundy, the Texas historians searched for documentary evidence of a cabal of Virginia or North Carolina planters sitting down and painstakingly plotting the Texas revolution; finding no so such overt conspiracy, they protested that slavery had not been at issue in Texas’ fight for freedom.

Later historians have either passed swiftly over slavery in Texas or offered questionable apologia: The great majority of Texas farmers did not own slaves (although this was also true throughout the south); Slaves were treated better in Texas than in other southern states; Texans despised the planters and only voted for secession because they feared a slave uprising in the event of emancipation. No Texas historian has yet been able to suggest that the first generations of Texans were calculating, pragmatic opportunists, who, like Austin, embraced slavery in spite of its moral odium simply because it promised them prosperity and a better life.

Antebellum Texas was the booming frontier of the old south, its planter class too new and raw even to borrow the elegant neo- classical architectural veneer of the Deep South. Painting, never significantly patronized in the Deep South, was less so in Texas. Artists tended to visit Texas briefly, and to be interested principally in Indians and wildlife: George Catlin, the artist/explorer noted for his studies of American Plains Indian culture, made sketches of Comanche and Pawnee tribes in north Central Texas in 1834; John J. Audubon painted birds in the vicinity of Galveston in 1837; Seth Eastman, a career army office and indefatigable documenter of Indian culture, did meticulous drawings of the central Texas Hill Country while posted there as commander of a company of mounted infantry in the late 1840’s.

A few artists stayed. French immigrant Theodore Gentiltz, who had studied cartographic drawing in Paris, came to Texas in 1843 to help land promoter Henri Castro lay out the Alsatian community of Castroville. Gentiltz lived in San Antonio from 1845 until his death in 1906 and painted many faithful if uninspired local vignettes, but his interest was the inland city’s picturesque if impoverished Mexican community, far removed from the coastal cotton culture. (That throughout the antebellum South very few realistic images of slavery were recorded was not simply because artists found the subject uninteresting or unappealing. English artist Eyre Crowe, traveling in Virginia in 1853 as secretary to the novelist William Makepeace Thackery, described an incident in Richmond in which he attempted to sketch a slave auction and was driven away by an angry crowd.)

While Texas’ slaveholding empire left no cultural monuments, it has left the state a particularly enduring legacy. Virtually every artist in this exhibit has had to deal with the consequences of Texas’ origins as a slaveholding society: a stunted industrial base, which left Texas dependent on the vagaries of crops and climate until the 1930’s – and plagued with an economic inferiority complex that continues to this day; retarded urban development in the nineteenth century, followed by convulsive growth in the twentieth, both of which have left a deeply embedded mistrust of cities and their culture; and, of course, legally-mandated racial segregation so recent that even relatively young Texas-born artists can remember whites-only theatres and "colored" restrooms.

However, the point in revising the Texas Genesis is not to suggest that slavery is the original sin from which everything Texan must inevitably descend. It is simply to illustrate that Texas history, more so than most history, is a looking glass in which its subjects see themselves as they wish to be, not as they are. The image that Texans (and true believers in the Texas myth throughout the world) perceive of their past – and thus, of their present and future – is not merely tinted with rosy nostalgia, but is deeply distorted with fundamental misconceptions. The challenge for generation after generation of Texas artists has been to peer through the looking glass of history and find the scintilla of truth.

1886: "GEH MIT INS TEXAS"

By 1886, the Republic of Texas had been annexed by the United States of America, seceded from the union and fought on the side of the Confederacy in the Civil War, endured a bitter Reconstruction era, and had entered a period of populist reform. Settlement had pushed far beyond the original woodland crescent of 1836, into the arid high plains of west Texas. In the 1850 census Texas had ranked twenty-seventh among the states in acreage under cultivation; in 1900 Texas would rank rank first in the nation.

Buffalo had already vanished from the plains and prairies by 1886, as had the Indians who relied on them for sustenance. The great Trail drives of Texas longhorn cattle to the railheads in Kansas, which had begun at the conclusion of the Civil War, were coming to an end, and barbed wire had begun to close off the open range of lore and legend; in 1884 the Texas Legislature passed a law making fence-cutting a felony. The shrewd acquisition and consolidation of real estate parcels had become more essential to success in ranching than frontier grit, and the Cattle Barons of the 1880’s were as likely to be European or Yankee capitalists as former trail bosses. Texas’ largest ranch, the Matador, was owned by group of Scottish investors.

Despite the growth of the cattle industry, cotton remained more important to the Texas economy; the value of the cotton crop throughout the era of the Cattle Kingdoms was typically fifty to one hundred percent greater than the value of beef cattle. Sharecropping had replaced slavery as a means of providing cheap agricultural labor; under the typical arrangement, the land owner received three-quarters of the crop, but because he also provided credit, he often ended up with the sharecropper’s quarter. Timber harvesting was also a boom industry; although the timber barons of east Texas were empire builders as adept at wheeling- and-dealing as their ranching counterparts, the romance of felling trees has not been incorporated into the Texas myth. Rail lines transformed the map of Texas, planting cities like Dallas in featureless prairie, while previously thriving communities that had spurned the railroads withered and died. By the beginning of the twentieth century Texas had more miles of track than any other state.

Hermann Lungkwitz, a graduate of The Royal Academy of fine Arts in Dresden, Germany, was 73 years old in 1886. He probably painted The Klappenbach Ranch near Johnson City [cat. #], two or three years earlier. The Central Texas sheep ranch was the home of Lungkwitz’s daughter, Eva, and her husband, Richard Klappenbach; between 1882 and 1886 Lungkwitz lived and helped out at the ranch, tending the vegetable garden, building rock walls for sheep pens, or keeping amorous rams away from the ewes. Lungkwitz’s oeuvre was curiously divided between such documentary images of frontier settlement – mills, farmhouses, and views of San Antonio and Austin – and the stirring, transcendental frontier landscapes that are his signature works. Yet a closer look at Lungkwitz’s life illuminates the passion he invested in even this small oil sketch. For Lungkwitz, these simple frontier structures were symbols of a profound and persistent faith, as charged with meaning as Casper David Friedrich’s mountaintop cathedrals and crucifixes.

Lungkwitz had arrived in Texas in 1851, joining a German immigrant population that numbered about 30,000 at the time – almost one fifth of state’s white population. The German federation had enjoyed a cultural florescence in the first half of the nineteenth century, but overpopulation, crop failures, and political repression prompted the exodus of millions of German farmers and intellectuals. The preferred destination was America, and more specifically, Texas. Between 1815 and 1850, more than fifty books were published by Germans who had traveled in the United States, and Texas was featured so prominently that Germany in the 1840’s was swept by a Teutonic strain of "Texas fever." This American enthusiasm, whetted by glowing reports in journals like De Bow’s Review, drew hundreds of thousands of immigrants to Texas from the Southern United States. Mostly small "yeoman farmers," precursors of the celebrated "redneck," these southern immigrants were the dominant demographic force in Texas throughout the nineteenth century. They brought with them a world view often quite different from that of the German immigrants, but they were brought to Texas by same potent myth of place.

In Germany, perhaps the most widely-read ode to Texas was Texas und seine Revolution (Texas and its Revolution), by Hermann Erhenberg, who fought in the Texas revolution before returning to Germany to teach at the University of Halle. Erhenberg’s book extolled the political liberties claimed by Texas’ white settlers – a notion with profound appeal to Germans starved for democratic reform. A lushly romanticized view of the frontier paradise of Texas was provided by the novelist Karl Anton Postl, who had traveled throughout the United States but had never visited Texas. Hoffman von Fallersleben, who wrote Germany’s national anthem "Deutschland uber Alles," was so captivated by the Texas mystique that in 1846 he published a collection of poetry titled Texanische Lieder (Texas Songs). In 1843 a group of German noblemen, prompted by both altruism and profit motive, established the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas, or Adelsverein, which settled almost ten thousand immigrants in Texas before going bankrupt in 1847. So persistent were the Adelsverein’s recruiting efforts that "Geh mit ins Texas"– "go with us to Texas" – was reported to have been a common greeting in some parts of Germany.

The son of a successful Dresden hosiery manufacturer, Lungkwitz entered the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in 1840. His principal teacher was Ludwig Richter, a second generation German romantic landscapist who eschewed the allegorical vistas of predecessors like Casper David Friedrich in favor of a more subtly reverential, intimate study of nature. Lungkwitz seems to have inherited his master’s low-key spirituality, making frequent sketching expeditions into the Alps after his graduation in 1843, returning with precisely rendered, meditative vignettes of mountain streams and antique ruins; some of Lungkwitz’s trees, drawn in almost compulsive detail, are as individualistic as portraits.

The suppression of Dresden’s democratic movement by the Prussian army in 1849 almost certainly motivated Lungkwitz’s decision to leave his homeland. Along with a party of five other family members, including his wife, Elise, and her brother Richard Petri, also an accomplished Academy-trained artist, Lungkwitz eventually settled on a 320 acre farm near Fredericksberg, a town founded by the Adelsverein in the picturesque Hill Country northwest of San Antonio. They were on the edge of the frontier; in 1852 Lungkwitz and Petri signed a petition imploring the Governor of Texas to police the Indians in the area.

Lungkwitz and his family worked hard to transform the wilderness into a garden. He built log cabins and rail fences, grew corn, and raised cattle, pigs, and chickens. The work was impeded by violent weather, drought, and disease; in December of 1857, Petri, feverish from what was most likely a recurrence of malaria, wandered into the Pedernales river and drowned. To supplement his meagre income from farming, Lungkwitz sold lithographs (one was an advertisement for a local "water-cure" health spa), raffled paintings, worked as a surveyor, and took up photography, briefly touring with a magic-lantern slide show billed as "brilliant Stereomonoscopic Dissolving Views and Polarscopic Fire Works." Lungkwitz’s landscapes were perfunctory, almost lifeless during this period; much more inspired was Crockett Street Looking West, San Antonio, (1857) [il. San Antonio Museum Association]. Lungkwitz depicted the sparkling little city, then Texas’ largest (pop. 8000), in a clean, brilliant, Mediterranean light, a miniature Athens rising from the dust.

The Civil War brought Lungkwitz face-to-face with some unpleasant truths about his adopted homeland. Most Germans were too poor to own slaves, and while some served in the Confederate army, most either declared their pro-Union sentiments, or, like Lungkwitz, adopted a silent "neutrality" that nevertheless left little doubt about their true loyalty. This made the Germans easily identifiable targets for Confederate enforcers. In 1862, four dozen German settlers who had refused to swear loyalty to the confederacy were massacred by Texas troops. Confederate "bushwhackers" roamed the area around Fredericksburg, murdering German settlers; on one occasion Lungkwitz’s wife hid him under her mattress and feigned illness while bushwhackers searched the house.

Fearing for his safety, Lungkwitz moved his wife and five children (a sixth was born by the war’s end) to San Antonio. Deeply depressed by what he called "this unholy war," Lungkwitz apparently renewed his passion for nature; in his Enchanted Rock near Fredericksburg (1864), the massive granite dome, purpled with the setting sun, stands like the indestructible cathedral of a timeless faith [il. (San Antonio Museum Association)]. At the war’s end Lungkwitz opened a photography studio with Carl von Iwonski, a Silesian immigrant and painter. (Largely self-taught, Iwonski painted some sharply insightful, technically accomplished portraits of his fellow German immigrants.) During Reconstruction, Lungkwitz was rewarded with a position as an official state photographer by the last Republican administration Texas would see for more than a century.

Lungkwitz lost his state job when the Republicans were voted out in 1874. He spent most of the years until his death in 1891 traveling between the homes of his married daughters and painting from nature with an autumnal fervor. His focus narrowed from broad panoramas to more tightly framed scenes similar to those he had favored during his youthful Alpine sojourns: rushing water, rock formations, gnarled trees. But now these scenes had a painterly spontaneity Lungkwitz had been unable to realize in his youth, along with a dynamic vision of nature unlike anything in the romantic tradition.

In Lungkwitz’s late works nature is no longer a timeless verity, a catalogue of marvels intended as metaphoric reminders of man’s transience, but rather an organism struggling with its own cycle of death, decay, and regeneration. Rocks are surrogates for both human and architectural forms: Veined with fissures and tinted like flesh with the sun, or eroded by water into drooping grotesques, they have a potent animism; limestone bluffs carved by rivers resemble the masonry ramparts of some antediluvian civilization. Lungkwitz often centered his compositions around pools, basins, grottoes, and caves [il. West Cave on the Pedernales 1883, McGuire #269]. Dark, still recesses in the midst of nature’s relentless motion, they are wells of metaphysical yearning, portals to some transcendental realm.

Although Lungkwitz’s work is well-known today in Texas, he remains a virtually unexamined anomaly in the broader context of nineteenth century American art. Much of today’s mythic image of the American west has evolved directly from German-born immigrant artists like the western genre/history painters Charles Wimar and Emmanuel Luetze, and the landscapist Albert Bierstadt, all three of whom studied at the Dusseldorf Academy, where they were inculcated with a classical, highly formalized, history-painting tradition. These three, along with artists of similar European academic training, such as Alfred Jacob Miller, Charles Deas, and Thomas Moran, wandered the west in search of authentic vistas and vignettes. Reproduced in magazine illustrations and lithographic reproductions sold in the tens of thousands by mass marketers like Currier and Ives, the work of the "westering" history painters (whose significant role in 19th century American art and popular culture is just beginning to be recognized) reached a huge urban audience on the East Coast. But the western icons the history painters invented – the noble savage, the "mountain man" [il. Charles Deas, Long Jakes, The Rocky Mountain Man (1844) (Vose Galleries of Boston, Inc.)], the virgin wilderness – were already anachronisms by the time they entered the popular imagination.

Uniquely among these skilled immigrant artists, Lungkwitz staked his claim to a tiny piece of the west and actually lived through its transformation from frontier to a rudimentary civilization (thus his evident reverence for farmhouses, mills, and even towns, the rudimentary monuments of that civilization). Unlike his history-painting peers, Lungkwitz didn’t try to re- invent the recent past as a series of Manifest Destiny fairy tales. Instead his work conveys an earnest psychological realism, the confessions of a settler’s often troubled soul. Doubt, fear, the loss and reclamation of faith – the spiritual crises and resolutions that animate Lungkwitz’s art – don’t make for stirring myth, but they illuminate the real forces at work on the frontier. Texas and the rest of the American West weren’t conquered by the heroic few, but by thousands, then tens and hundreds of thousands of tenaciously ordinary settlers like Lungkwitz, who left their homes to build new homes, who buried their friends, wives, husbands, and children in foreign soil, who overcame despair, cowardice, and uncertainty to create a new world.

In 1886, Frank Reaugh was sketching round-ups of Longhorn cattle on the grassy plains just south of the Red River (which separates Texas from Oklahoma) in north central Texas. Born in 1860 in Illinois, Reaugh had come to Texas with his family in 1876, traveling by covered wagon. The family had settled on a small farm thirty miles east of Dallas, a region of fertile black soil that remained unfenced, open range; the Reaugh farm was surrounded by herds of Longhorn cattle, brought from sparsely vegetated South Texas to fatten up before moving on to the Kansas stockyards. According to Reaugh’s own account, he was already determined to be an artist by the time he arrived in Texas, and although he had yet to see an original painting or a reproduction in color, he was familiar with monochrome engravings and lithographs of works by Camille Corot, J.W.M. Turner, Edwin Landseer, and Rosa Bonhuer.

Reaugh became captivated by the Longhorns, a lanky, hardy breed descended from cattle brought into South Texas by Spanish settlers. He approached the subject with monomaniacal intensity, poring over a book on bovine anatomy, collecting, measuring and drawing cattle skeletons, and sketching live Longhorns whenever he could free himself from his farm work. In the early 1880’s Reaugh left the farm to follow the herds, sketching roundups and trail drives. He received his first formal training in St. Louis in the mid-1880’s. Later in the decade he was a student at the Academie Julien in Paris, then went on to Holland to independently study the work of the Dutch landscape painter Anton Mauve, a painter of atmospheric, carefully observed landscapes in the tradition of the French Barbizon school. (Mauve also briefly tutored his nephew, Vincent Van Gogh.)

Reaugh’s early pastels (the medium he preferred because it most faithfully reproduced the "opalescent" light of the prairie) were remarkably authentic – and to modern eyes, surprising – images of nineteenth century rangeland. Cross Timbers Twilight [il. Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin)] depicts a region of north central Texas where woodland and grassland meet; the lush, brooding, backlit scene might have been sketched in the forest of Fontainebleau.

By the time Reaugh returned from Europe, the trail drives were over and the Longhorn, whose imposing horns and feisty temperament made it difficult to load into railroad cattle cars, was obsolete, soon to be usurped as Monarch of the Plains by the more compact and docile English Hereford. The end of the trail drives also coincided with the last, feeble Indian uprising in the United States, which ended with the massacre of 300 Sioux warriors, women, and children at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota on December 29, 1890. The 1890 Census of the United States underscored these milestones by declaring the frontier officially closed; the population figures revealed an America settled from sea to shining sea, the fulfillment of the Manifest Destiny of the Anglo-American people to bring the light of civilization into the wilderness.

Post-frontier America had its coming-out party at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. The colossal steel-truss palaces of the great White City (among them the largest roofed structure ever built) glittered with the most extensive display of incandescent lighting on the planet, proclaiming the transformation of America from a struggling agrarian democracy to an industrial superpower. Yet as America rushed headlong into the future, it also began to look back with nostalgia at its vanished frontier. The most popular attraction in Chicago in 1893 was Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show, which ran for more than 300 performances just outside the fairgrounds.

Cody’s theatrical revival of the wild west also had a more serious intellectual counterpart. The Columbian Exposition hosted a World’s Congress Auxiliary, a series of conferences on subjects ranging from Art to Temperance. At the Congress of Historians, a young professor from the University of Wisconsin, Frederick Jackson Turner, presented his paper "The Significance of the Frontier in American History." Turner disputed the reigning orthodoxy that American culture represented the "germination" and fruition of European civilization in a new world. What Turner saw was a radically new society whose distinguishing characteristic was the frontier. "The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American civilization westward, explain American development," Turner declared. "This perennial rebirth, this fluidity of American life, this expansion westward with its new opportunities, its continuous touch with the simplicity of primitive societies, furnish the forces dominating American character."

Within a few years Turner’s "frontier theory" had been reprinted widely and had become the subject of nationwide discussion, an influence that steadily waxed throughout the first quarter of the twentieth century. While Turner’s assumptions are being re-examined by today’s scholars, they have lost little popular appeal; the continuing invocation in late twentieth century America of the ideals of a frontier democracy has its foundation in Turner’s thesis. And the influence of Turner’s thinking on Texas mythologizers has been particularly profound. George P. Garrison’s Texas: A Contest of Civilizations, published in 1903, and Westward Extension (1906) proceeded directly from Turner’s thesis. Garrison’s disciple Walter Prescott Webb, Texas’ most venerated historian, adapted Turner’s ideas into an original vision that is likely to define Texas into the twenty- first century.

Frank Reaugh also had his moment on the stage at the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893. He was one of a handful of western American artists represented in an enormous international exhibition (more than 1000 works by American artists alone) in the sprawling, neoclassical Art Palace. Reaugh sold two pastels from the exhibition, and continued to show his work to enthusiastic reviews in Chicago and St. Louis for at least another decade. But Reaugh’s vision of the open range was soon overshadowed by that of another Columbian Exposition artist, Harper’s Weekly illustrator Frederic Remington.

Born and raised in Canton, New York, Remington studied art at Yale, then embarked on a brief and unsuccessful western sojourn, failing as both a Kansas sheep rancher and saloon keeper before returning home. Remington resided in New York for the rest of his life, but he made periodic trips west (preferring to go as far as possible by Pullman car), often to report on various military expeditions; he was in the vicinity during the Wounded Knee massacre, and gave Harper’s Weekly a glowing account of the troopers’ heroism – which he hadn’t witnessed and which hadn’t occurred.

Harper’s Weekly assiduously exaggerated Remington’s actual experience of the west he portrayed, promoting their star artist as a veteran Indian fighter; by the turn of the century Remington had become the most widely recognized artist in America. In the mid 1890’s Remington and his frequent collaborator, the Philadelphia-born, Harvard-educated novelist Owen Wister (Virginian), took a little-known western laborer, the "cow-boy," and re-cast him as the new American frontier hero, the successor to the mountain man of the 1850’s. The paradigm perfected by Remington and Wister in their articles, books, bronzes, and paintings became a fixture in illustrated magazines and pulp novels in the first decade of the twentieth century, was soon appropriated by the nascent motion picture industry, and today remains the most identifiable American icon.

Reaugh had his own opinion of Remington: "He knew little about cows and was principally interested in the cowboy as wild man." The two artists offered an interesting contrast. Reaugh did all of his sketching and much of his painting in the out-of- doors, while Remington traveled with a Kodak camera and did most of his painting from photographs in his New York studio. Remington’s west was arid, the sunlight harsh, almost acidic, etching shadows into the sere earth; on one of his trips west he found West Texas too green for his taste and ventured into New Mexico and Arizona before he found the kind of sun-baked, ochre landscape he preferred. Reaugh depicted the open range as it was in the cowboy’s day, before fenced-in cattle stripped the tall grass: a hazy, panoramic prairie of rich olive hues punctuated with bursts of pink and yellow wildflowers and wooded islands of cool, blue greens. Remington’s west is a place of ceaseless motion and conflict [il. A Dash for the Timber (Amon Carter Museum)], while in Reaugh’s west the herds proceed across the plains in gentle, stately serpentines [il. Driving the Herd (Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin)].

Reaugh was actually the realist and Remington the romantic, but Remington’s dramatic macho style met popular expectations of the wild west. Reaugh disappeared from the national arena after the turn of the century, but he had a more enduring influence as teacher to several generations of Texas artists. Reveau Bassett [cat #] and Edward Eisenlohr [cat. #], both atmospheric landscapists in the Reaugh tradition, accompanied Reaugh on his annual sketching expeditions to the high plains of West Texas. Alexandre Hogue, the most important Texas artist of the first half of the twentieth century, also went west with Reaugh and his students in the 1920’s. But Hogue would see the plains with a radically different vision; between Reaugh and Hogue, the Texas landscape leaps from the nineteenth century to the twentieth.

The nineteenth century in Texas art most properly closes with the sudden death of Julian Onderdonk at age forty in 1922. Julian was the son of Robert Jenkins Onderdonk, scion of prominent Maryland family and a founding member of the New York’s Art Student’s League. Robert Onderdonk came to San Antonio in 1879 intending to get rich quick painting portraits of local plutocrats, but he stayed to become an influential teacher in San Antonio and Dallas. The senior Onderdonk tried his own hand at the Texas Myth; when he undertook The Fall of the Alamo [pl. #] he wrote his patron that Davey Crockett’s death would be recorded with scrupulous regard for the facts: "I suppose you know that Crockett was not killed in the Alamo but in defending the gateway of a building in the first assault."

Julian Onderdonk left his native San Antonio in 1901 to study at the Art Student’s League under William Merritt Chase; he returned in 1909 in possession of a workmanlike impressionist style [cat #’s] that slowly matured as he painted views of the same south central Texas Hill Country that had stirred Lungkwitz. Onderdonk’s amethyst-hued bluebonnet fields inspired enough imitators to create a popular art cottage industry that still thrives in Texas today, cranking out derivations so hackneyed that they have tainted the originals. (Onderdonk lived long enough to despise his designation as the "bluebonnet painter.")

But Onderdonk’s wildflowers were only the pretext for an increasingly subtle and spiritually resonant late Impressionist style. In Onderdonk’s last picture, Dawn in the Hills (1922) [il. (San Antonio Museum Association 38-18-69 P)] the shrouded, flickering hills and a pale sun struggle to materialize through an elegiac, dusty purple mist. As with Lungwitz’s late work, in Onderdonk’s culminating vision nature is merely an evanescent veil over a deeper mystery; one is tempted to project intimations of mortality on the scene. The imminent death in Onderdonk’s final opus, however, is not only that of the artist but of the land itself.

1936: THE CRUCIFIED LAND

In 1936, Texas provided almost forty per cent of all the oil produced in the United States. The oil age had arrived with a new century, when the fabled Spindletop well blew in on January 10, 1901, sending a geyser of black crude one hundred and fifty feet into the air, in nine days creating a lake of oil equal to Texas’ entire oil production the previous year. The most immediate effect of the oil bonanza was to put people and money into Texas’ cities, none of which had claimed more than 60,000 inhabitants on the day Spindletop blew; by 1930 Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio all exceeded 200,000, and by 1938 Houston would top 400,000. The social elites of the burgeoning cities began to be dominated by oilmen and their financiers. In Houston, the uncouth Wildcatter vied for supremacy with more gentlemanly oil magnates whose fortunes had been established through interest in Humble Oil and Refining Company, Texas first major oil company, which had prospered in a largely silent partnership with John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New Jersey. Adhering to an eastern seaboard ideal of wealth without ostentation, Houston’s "old money" families, who had established the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in 1924, would for many decades run Houston’s cultural institutions with same innate conservatism that they did their lives and businesses.

Politically, Texas had assumed a pattern it would follow for the rest of the twentieth century: episodes of progressive reform alternating with episodes of conservative, sometimes virulent retrenchment. In the opening decades of the twentieth century the Texas legislature passed some of the nation’s first child labor laws and extended suffrage to women in advance of the nineteenth amendment to the United States constitution. But in the 1920’s the Ku Klux Klan became a powerful broker in Texas politics, and the state legislature voted to permit the exclusion of black voters from primary elections.

Reform forces had surged back by 1936; the second-term governor of Texas, James Allred, advocated a commission to regulate public utilities, cleaned up corruption in the Texas Rangers, and crafted an old age assistance package. Texans were also some of the prime movers of the New Deal in Washington. Vice President of the United States John Nance Garner, a former congressman from the south Texas town of Uvalde, held conservative Democrats in an uneasy accommodation with President Roosevelt. Sam Rayburn was in his twenty-fourth year as a congressman from a rural East Texas district; a true Texas populist, Rayburn had already authored some of the most important New Deal legislation. Houston banker Jesse Jones headed the key Reconstruction Finance Corporation. And twenty-seven year old Lyndon Johnson, most recently a congressional assistant, had just been appointed to run the National Youth Administration in Texas.

As much as Texas had progressed between 1886 and 1936, it remained an agrarian culture, with two thirds of all Texans still residing in rural areas and agriculture still claiming two thirds of all employment and investment. Cotton continued to be not only the dominant crop but a rival to oil as the driver of the Texas economy. Not until the discovery of the East Texas oil field in 1930, at the time the world’s largest known oil reserve, did the cash value of Texas’ crude oil production finally exceed the value of the cotton crop – and then only because of a precipitous plunge in the price of cotton. Almost 70% of all farmers were sharecroppers, the great majority of whom, white and black alike, cooked on wood stoves and lit their homes with oil lamps. But the collapse of cotton prices, combined with the relentless "Dust Bowl" winds that stripped away soil already scourged by drought, overgrazing, and overproduction of cotton, had initiated a mass exodus from the land. In 1935 the number of farms in Texas had peaked at half a million. By 1960, that figure would be halved.

Despite the ravages of the Great Depression, in 1936 Texas concluded a remarkably sophisticated – and successful – effort to merchandise its sacred history. The event was the Texas Centennial Celebration, a multi-million dollar statewide extravaganza culminating with a "World’s Fair" in Dallas. Promoted by Hollywood stars, a traveling troupe of "Rangerettes" attired in chaps and five gallon hats, and a nationwide press junket highlighted by Texas Ranger Captain Leonard Pack, who rode into the lobby of a Detroit hotel on his horse, Texas, a Colt six-shooter on each hip, the Centennial was shrewdly conceived by Texas advertising and publishing executives as a public relations opportunity for the entire state. The basic selling tool was Texas’ celebrated past, which Centennial boosters believed would lure tourists and investors capable of enriching Texas’ future. Governor Allred’s proclamation inaugurating the centennial year was a credo for Texas’ new aspirations: "As we stand upon the threshold of our State’s Centennial, we must not forget that its purest concept lies in reverence for the past, and a devotion to the perpetuation of that past through an endless future."

Among the sleek, thirties-moderne buildings constructed for The Texas Centennial Exposition was a new Dallas Museum of Art, which until then had been housed on the ninth floor of a local office building. The museum opened with a survey of art from the Renaissance through Picasso, but the most talked-about feature of the Texas Centennial exhibit was the sharply delineated regional style evident in a juried selection of almost 200 works by Texas artists. This unprecedented regional movement (perhaps best referred to as "Lone Star Regionalism," the title of the definitive 1986 exhibition and catalogue by historian Rick Stewart) coalesced around a loosely affiliated but ideologically focused group of local artists known as the "Dallas Nine."

The centerpiece of the Dallas exhibit was Drought Stricken Area [cat #] by Alexandre Hogue, the most talented artist among the Nine and, along with Dallas painter and critic Jerry Bywaters, the movement’s most outspoken proselyte. Painted in 1934, Drought Stricken Area is an almost viscerally evocative Dust Bowl landscape, a scene, in Hogue’s own words, of "realism more real than the thing itself." The painting is a composite of symbolic attributes as carefully arranged as a Dutch still life: the fractured geometry of the windmill (first used widely in the 1870’s to pump water from deep wells, windmills remained ubiquitous high plains landmarks in the 1930’s) echoing the arc of the half-buried water tank; the dismantled fences marking the breakdown of a transient human order; the vulture waiting to reclaim the emaciated cow, the last vestige of civilized husbandry. Hogue suggested atmosphere by its absence; not only moisture but the air itself seems to have been sucked out of his razor-edged landscape.

Born in rural Missouri, Hogue was brought to Texas as an infant just before the turn of the century. He studied art in New York for four years in the early 1920’s, returning to Texas each summer to ride west in Frank Reaugh’s model T truck. For a time Hogue painted in Taos, but he eventually eschewed that picturesque landscape for the "still waters" of Texas’ "rolling plains," which he believed offered "extraordinary possibilities for the painter who masters interpretation of them."

Hogue became both a scenic and an ideological interpreter of the Texas landscape. By the late 1920’s he was a regular contributor to the Southwest Review, which had become the mouthpiece for a broadly based regional movement that encompassed art, architecture, literature, and music. Hogue protested that most young American artists were "following the European herd," and could never hope to achieve real stature until they made art based on their own experience; Hogue perceptively cited Cezanne as an artist who succeeded by becoming a regionalist, immersing himself in the provincial landscape of Aix en Provence.

Yet in choosing West Texas as his Aix en Provence, Hogue contributed to a sweeping redefinition of Texas itself. Significantly, this new incarnation of the Texas myth took place at the moment when oil replaced cotton as the engine of the Texas economy, allowing Texans for the first time to truly differentiate themselves from the militarily and economically defeated Old South. Suddenly Texas could discard its Confederate past and embrace a far more promising alliance, the New Southwest.

As early as 1929, Henry Nash Smith, a professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, had written about a "Southwestern ‘Renaissance’" in the Southwest Review. But the Southwest as an intellectual construction was not fully formed until the publication in 1931 of Walter Prescott Webb’s The Great Plains, a work of such importance to the Lone Star Regionalists that Bywaters opened his commentary on the Texas Centennial exhibition, published in the Southwest Review, by citing the central thesis of Webb’s book.

Webb was a forty-three year old professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin when he published the The Great Plains. His personal saga has added to his mystique, and doubtless colored his own view of Texas and the west. Webb’s father was a Mississippi farmer/schoolteacher who emigrated to Texas in 1883, settling in the wooded northeastern region of the state, a culture dominated by cotton and post-Civil War bitterness. In 1892 the family moved farther west, out of the woodlands onto the edge of the arid high plains, where Webb’s father taught school to the children of dirt-poor farmers; Webb himself had to drop out of school for two years to work the family’s 120 acres. At age 16, Webb wrote a plaintive letter to an editor of The Sunny South magazine, asking how he might go about attending college and becoming a writer. The published letter brought a response from a philanthropic New York novelties importer, who sent Webb books and magazines and eventually financed his education at the University of Texas.

In The Great Plains Webb essentially one-upped Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier theory of American history. Turner had claimed that American civilization was distinguished from its European antecedents by the continuous conquest of a western frontier. Webb, in turn, posited that the settlers of the great western plains, those pioneers who ventured beyond the timbered frontier east of the 98th meridian, had been confronted with entirely different challenges on the treeless plains and as a consequence had been forced to invent a culture as distinct from that of the Eastern United States as America was from Europe. The lord of this super-frontier was a new sort of knight-errant: "It would be hard to find a more effective ensemble of power," Webb wrote, "than a man on a good horse armed with a six-shooter – the one to conquer space, the other to conquer danger."

Webb’s designation of the 98th meridian as where the west began eliminated the entire eastern half of Texas, but that radical surgery made it easy for the dean of Texas historians to ignore the cotton culture of the Texas woodlands and coastal plains. Instead, Webb could view the state’s history as a matter of exterminating Indians and Mexicans, finding water, and raising cattle. The quintessential hero of the great plains rode forth in Webb’s 1935 book The Texas Rangers, a grotesquely reverential history of Texas’ traditional frontier policemen, whose reputation for gritty valor ("one riot, one ranger") was matched only by an appalling record of extralegal violence: The number of innocent Texans of Mexican descent summarily executed by Rangers during World War I, when the border was rife with rumors of Mexican-German conspiracies, has been estimated at anywhere from several hundred to five thousand. Black Texans, who comprised perhaps a fourth of all Texas cowboys, nevertheless didn’t figure much in Webb’s heroic vision of the Southwest. He had dismissed them in a 1916 student paper: "the negro must find his place and realize that he is a distinct, separate, and inferior caste…"

In later years Webb seemed to regret his racism and the overly broad strokes with which he had painted the heroic west, but by then the myth he had had a singular role in creating was far more powerful than he was. And while Webb offered Lone Star Regionalism a certain intellectual legitimacy, a closer look at his thought in relationship to the art movement reveals some of the differences that over time have estranged Texas art from Texas history.

Webb’s mythic west was the exclusive domain of Anglo- American males ("the plains repelled the women as they attracted the men…" Webb declared), while Lone Star Regionalism envisioned a much more inclusive new Southwest. Instead of viewing Mexico as a degenerate old world culture, routed by the heroes of the Texas revolution, and against which the noble Rangers had since maintained a necessarily ruthless vigilance, Hogue and Bywaters saw in the Marxist Mexican muralists of the 1920’s an example to be emulated. Bywaters met Diego Rivera during a 1928 trip to Mexico, afterward writing "Diego Rivera has taught me a lesson I had not learned elsewhere in Europe or America. I know now that art, to be significant, must be a reflection of life; that it must be understandable to the layman…" In a 1932 interview, Hogue praised the Mexican muralists for their "translation into art forms of intimate colloquial life…"

The Lone Star Regionalists also found inspiration in local diversity. Otis Dozier, another important member of the Dallas Nine, grew up on an east Texas cotton farm, and he later painted sympathetic portrayals of the sharecroppers’ plight as well as dignified scenes of Dallas’s black community. Dozier’s The Annual Move [il. Dallas Museum of Art], exhibited at the Texas Centennial in 1936, poignantly depicts a Central Texas sharecropping family stoically moving on to new land and new debt – an acknowledgement of the quiet heroism to be found east of the 98th meridian.

Webb idealized the nineteenth century cattle industry, writing in The Great Plains that "existence of the cattle kingdom is the best single bit of evidence that here in the west were the basis and promise of a new civilization unlike anything previously known to the Anglo-European-American experience." But the spiritual roots of Lone Star Regionalism lay in the far less aristocratic tradition of Texas rural Populism and farmer’s movements dating back to the Greenback Party of the 1870’s and the Southern Farmer’s Alliance of the 1880’s.

Texas Populism had a strong base in evangelical Protestantism, and revival meetings remained a fixture of rural life in the 1930’s. This bedrock spirituality led a number of the most important Lone Star Regionalists to depict the Depression as a kind of rural Passion drama. The fencepost crucifix motif established in The Three Crosses (1935-36) [il. (Dallas Museum of Art)] by William Lester, one of the younger members of the Dallas Nine and former student of Hogue’s, is central to Hogue’s The Crucified Land (1939) [il. Gilcrease Institute, Tulsa.], in which the red soil, eroded as a result of straight-line plowing, flows like blood. Everett Spruce’s Mending the Rock Fence (1936) [il. (Meadows Museum, Dallas)] has a Biblical seriousness; the bearded elder instructs a younger farmer as if passing on a ritual of faith.

The echoes of Italian quattrocento painting evident in Spruce’s work, combined with a modernist affinity for abstract geometric relationships, is characteristic of the stylistic breadth of Lone Star Regionalism. In this they were distinguished from the orthodox "American scene" painters like Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, who had become national celebrities (Benton made the cover of Time magazine in 1935) by vehemently rejecting European modernism in favor of a home-grown heartland esthetic. The Lone Star Regionalists welcomed the attention to regional issues attracted by Benton, Wood, and the rabidly chauvinistic critic Thomas Craven, but they chafed at the notion that the Texas movement was derivative. Hogue and Bywaters took pains to point out that, unlike the American scene painters, they had no intention of purging American art of all foreign and modern influences; they also found the cornbelt Americanism of Benton and Wood, which came close to caricature, to be a contrived and unauthentic form of regionalism.

Lone Star Regionalism continued to be strongly cohesive until the outbreak of World War II, and by the late 1930’s the Texas movement had achieved significant exposure. In 1937 Hogue’s work was featured in Life magazine, and one of his Dust Bowl paintings was purchased by the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris. In 1939 the Dallas Nine also figured prominently in two major shows on opposite coasts, The Golden Gate Exposition in San Francisco and the New York World’s Fair. Locally, the Dallas artists had established a sophisticated infrastructure, organizing a printmaking cooperative called Lone Star Printmakers, with the objective of making their images available to a broader audience; they also successfully lobbied for federal government public arts commissions and one-person exhibitions of Texas artists at the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts (Bywaters became director of the Museum in 1943).

World War II finally brought down the curtain on Lone Star Regionalism. By the late 1930’s Hogue had already presaged a new Texas in paintings based on the oil industry [il. Mural, Post Office, Graham, Texas], which had moved strongly past cotton as the dominant force in the Texas economy even before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. In 1942 Hogue went to work as a technical draftsman for North American Aviation, which had just built the world’s largest single-building industrial facility near Dallas; Hogue was soon making lithographs of the Liberator bombers that were pounding Axis oil refineries [.il Oil Strike (Dallas Museum of Art)]. The war and its aftermath transformed the Texas economy and landscape as oil alone never could have, creating the petrochemical and defense industries that brought Texas fully into the twentieth century. What the Lone Star Regionalists recorded with striking emotional authenticity was the anxiety, nostalgia, and wary hopefulness of a culture poised on a demographic fulcrum; the 1940 census would be the last in which more Texans were found to reside on the land than in cities.

Lone Star Regionalism remains the pivotal episode in the history of Texas art, linking the nineteenth century romantic realism of Lungkwitz to the allegorical expressionism of Texas art a century later. But the Lone Star Regionalists are perhaps closer to the present than they are usually credited (Indeed, Hogue is still active). In their populist outlook, broad stylistic synthesis, direct yet sophisticated use of readily identifiable, colloquial symbols, and their quest for a pluralistic Texas myth, the Lone Star Regionalists anticipated the defining features of Texas art today.

1986: ON THE POSTMODERN FRONTIER

In 1986 the price of crude oil plunged to under fourteen dollars a barrel, unmistakably punctuating the end of one of the most extraordinary periods of sustained economic expansion in the history of the United States. While most Texans viewed the oil bust as the abrupt end to an equally sudden prosperity, the oil boom of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s was in fact the climactic spike in a growth curve that had begun its steep ascent with the outbreak of World War II.